Prelude to Forgiveness

Third Sunday in Lent 2016

Luke 23: 32-43

I have a colleague and a friend who told me that after the Charleston church massacre he was talking with someone who told him that he thought it was weak for the families of the slain victims to forgive their murderer at his hearing. Rick said, “I found it most inspiring.” “Well you would, wouldn’t you?” he said, “You’re a Christian!”

I have a colleague and a friend who told me that after the Charleston church massacre he was talking with someone who told him that he thought it was weak for the families of the slain victims to forgive their murderer at his hearing. Rick said, “I found it most inspiring.” “Well you would, wouldn’t you?” he said, “You’re a Christian!”

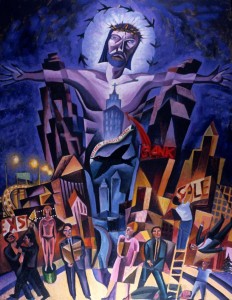

When I hear things like that I realize that I as a Christian take certain things for granted that are not shared by everyone. I’d like to think I would have been able to forgive as those family members forgave, or at least know it is what I should do. But forgiveness is a scandal, even to people within the church. A pastor in a suburb of New York City the week after the 9/11 attacks preached on forgiveness. A number of people in their community, like many others surrounding New York, died when the World Trade Center towers collapsed. The pastor was fired for the sermon on forgiveness. Not fired in the corporate “clean out your desk” sort of way, but in the discreet way that upper middle-class folks do it. It only took a few influential members stirring the pot, but in a matter of weeks the pastor was gone and the congregation was told that he was called to “new fields of service.” The irony, of course, is that at the center of that church’s worship space was a cross, a reminder that Jesus died forgiving those who murdered him. It’s still a scandal.

That’s why this story is so powerful. Even though I’ve heard it hundreds of times, you could knock me over with a feather. I still find it astonishing that Jesus could say, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” I mean God sent the very best, the Son of God, Jesus, a man who lived among the people, loved them, cared for them, taught them, ate with them, laughed with them, healed their sick, taught them the Good News of the Kingdom—and they killed him for it. The best that the world had created, both in the politics and society of Rome and in religion with the monotheism of Judaism, turned on him and executed him. Yet he could still say, “Father, forgive them.”

We’d like to think that Jesus was able to do that because he was in some way divine. But I like to think that Jesus was the model of what God really intended human beings to act like. We are to be merciful, forgiving, and compassionate. But it’s so hard. I suppose that God can forgive instantaneously, but we’re not God. God can separate our sins as far as the east is from the west and remember our transgressions no more. But it doesn’t happen like that for us, does it?

I think the Church hasn’t always been realistic in its teaching on forgiveness. We can’t forgive instantaneously, yet most teaching and preaching makes us feel guilty if we don’t. We can forgive unintentional slights and mistakes, but the big hurts, the betrayals, the unfaithfulness—those are the hard ones to forgive. We feel the pain deeply. We rehearse the hurt over and over again. We fantasize about revenge.

What I’ve concluded after dealing with fallible human beings for decades and as a fallible human me, is that forgiveness is a process and in some cases it is a process that might take a lifetime. I resonate deeply with that. Lewis Smedes in his book Forgive and Forget: Healing the Hurts We Don’t Deserve says there are distinct stages that we need to go through before we can really forgive.

First of all we hurt. And we have to own the hurt; we can’t deny it. I’ve lived long enough to know that you will eventually be hurt by someone you counted on to be your friend. We can only forgive people: we can’t forgive nature like an earthquake or a hurricane or systems like the IRS even though these can hurt us. We don’t need to forgive people who haven’t hurt us. In fact, we have no right to forgive them; only their victims have that right. It’s even harder when people hurt us unfairly. There is pain and then there is unfair pain. It hurts to lose $50 on a fair bet; it also hurts to be mugged on the street and robbed of $50. It hurts to be bawled out for hitting your sister; it also hurts for a child to be screamed at by a drunken father.

First of all we hurt. And we have to own the hurt; we can’t deny it. I’ve lived long enough to know that you will eventually be hurt by someone you counted on to be your friend. We can only forgive people: we can’t forgive nature like an earthquake or a hurricane or systems like the IRS even though these can hurt us. We don’t need to forgive people who haven’t hurt us. In fact, we have no right to forgive them; only their victims have that right. It’s even harder when people hurt us unfairly. There is pain and then there is unfair pain. It hurts to lose $50 on a fair bet; it also hurts to be mugged on the street and robbed of $50. It hurts to be bawled out for hitting your sister; it also hurts for a child to be screamed at by a drunken father.

There once was a person in my life who did outrageous things to me. She screamed at me all through dinner. She made me jump to her service at anytime, day or night, no matter how busy I was with other things. Now and then she would pee on my best pants. To make matters even worse, she would get acutely sick and scream. She drove me mad because she would not tell me what was wrong. I sometimes had the impulse to whack her, but never to forgive her. She was my 6 month old daughter Anna. I didn’t need to forgive her, just love her.

That is an example of unfair pain. But what if your husband of 25 years walks out on you for a knockout because you’re getting a little chunky where there once wasn’t any chunk, or if a business partner swindles you out of a life’s savings, or if your best friend begins to spread malicious lies about you—those are wrongful actions and they hurt. So the first step towards forgiveness is that we hurt. What else do we need to do?

I know this sounds totally unchristian, especially coming from a pastor, but we hate.

Note, I didn’t say we MUST hate, but that we do hate. Hate is a grizzly bear snarling in the soul. Hate is our natural response to any deep and unfair pain. Hate is our instinctive backlash against anyone who wounds us wrongly.

As I see it there are two kinds of hate most of us experience. One is passive hate. Passive hate is when we lose our ability to wish someone well. We don’t wish they would be hit by a bus, but we have a hard time praying that God would bless them. Then there is active hate. This is when we wish our unfaithful spouse would get herpes or that the friend who gave away your secret would get fired from her job. It’s when you actively wish someone ill. What makes this even more complicated is that it is people we hate, not merely evil. We often glibly say, “Hate the sin, but love the sinner,” but how is that possible? I don’t hate cruelty; I hate cruel people. I don’t hate treachery; I hate traitors. But in a way, when we do that we are complimenting them.

As I see it there are two kinds of hate most of us experience. One is passive hate. Passive hate is when we lose our ability to wish someone well. We don’t wish they would be hit by a bus, but we have a hard time praying that God would bless them. Then there is active hate. This is when we wish our unfaithful spouse would get herpes or that the friend who gave away your secret would get fired from her job. It’s when you actively wish someone ill. What makes this even more complicated is that it is people we hate, not merely evil. We often glibly say, “Hate the sin, but love the sinner,” but how is that possible? I don’t hate cruelty; I hate cruel people. I don’t hate treachery; I hate traitors. But in a way, when we do that we are complimenting them.

By that I mean, we hold them accountable as free moral agents. They are valuable human beings responsible for their behavior. What we do or not do matters. But hate unchecked will be your undoing. We can’t deny our hurt or hate, but if we let is stay there it is like a carcinoma that will eat you alive from the inside out; it will rot your soul. So, that’s why we need to take the next step.

We need to heal ourselves. When we begin to forgive someone for hurting us, we perform spiritual surgery of the soul. You cut away the wrong done to you so that you can see your “enemy” through a different set of eyes that can heal our souls and we receive several gifts.

One gift we receive when we begin to forgive someone is new insight. We see a deeper truth about them—they are weak, needy, fallible human beings, not ogres or monsters. They are not only people who hurt us; that is not the deepest truth about them. They are someone’s husband or wife, mother or father, and worker, friend who likely received their share of bumps and bruises in life that made them the way they are.

One gift we receive when we begin to forgive someone is new insight. We see a deeper truth about them—they are weak, needy, fallible human beings, not ogres or monsters. They are not only people who hurt us; that is not the deepest truth about them. They are someone’s husband or wife, mother or father, and worker, friend who likely received their share of bumps and bruises in life that made them the way they are.

And new insight often leads to new feeling. When you forgive me, the wrong I did to you becomes irrelevant to how you feel about me now. The pain I once caused you has no connection with how you feel about me now. We cannot pry the wrongdoer from the wrong; we can only release the person within our memory of the wrong.

The ancient drama of Judaism illustrates this. During Passover, the priest would lay his hands on a scapegoat that was released into the wilderness, taking the sins of the nation with it. It is poetic imagery of what happens in God’s mind. God’s memory changes. What we once did is irrelevant to how God now feels about us. Forgiving is an honest release, like the scapegoat, even though it is done invisibly.

The question naturally arises, how do we know that forgiveness has really begun? I think it begins when you recall those who hurt you and can honestly wish them well. Then you can begin to come together. That’s what we really want after all, isn’t it? Reconciliation. A coming together. One theologian I like said forgiveness is the active process in the mind of the wronged person where he or she lets go of the “moral hindrance” that’s breaking fellowship with the wrongdoer. After that, the freedom and happiness of friendship can begin to be re-established. In other words, the wrongdoer must be given an opportunity to prove his or her trustworthiness again.

But, you protest, what if that isn’t possible? What if the person doesn’t want to be reconciled? Or what if it’s too dangerous as when a parent abuses a child or a husband abuses a wife? Or a criminal who robbed you? That’s correct. Sometimes it is impossible to be reconciled to some people or it’s simply too dangerous to your mental or physical health. They may never be able to treat you in a trustworthy manner. It’s best to stay away. But with God’s grace you can begin to heal nonetheless by letting it go piece by piece until you can one day wish the wrongdoer well instead of harm.

But, you protest, what if that isn’t possible? What if the person doesn’t want to be reconciled? Or what if it’s too dangerous as when a parent abuses a child or a husband abuses a wife? Or a criminal who robbed you? That’s correct. Sometimes it is impossible to be reconciled to some people or it’s simply too dangerous to your mental or physical health. They may never be able to treat you in a trustworthy manner. It’s best to stay away. But with God’s grace you can begin to heal nonetheless by letting it go piece by piece until you can one day wish the wrongdoer well instead of harm.

We also have to remember if we simply brush off the wrong or pretend it didn’t really matter, we are taking our first step into an amoral life where nobody gives a rip about anything. We can’t treat people poorly with impunity and never have someone call us on our behavior. But things will never be right between us if we ignore the wrong between us.

In other words, the one wronged had to give up their claim on the other person and accept some kind of incremental payment plan of restored trust. In effect, you’re saying, “Let’s have a relationship again. I won’t hold the injury over your head and you prove to me that you’re worthy of my trust.” It means turning it loose and risking entering a relationship again, knowing that you may have to forgive again and again.

My friend Mary Luti says that when she’s to name Christianity’s most distinctive practice she always say forgiveness. Some people object. Not love? Doesn’t Paul say love is the greatest of all? Won’t it be the last thing standing when all is ended? Yes, she says, but I am certain that on the day of love’s triumph, it will appear in the shape of a dazed enemy inexplicably pardoned.

This is tough stuff and no one says it’s easy. But it’s better than the alternative of living with hate, bitterness, anger, and hurt all your life. That doesn’t hurt the person who hurt you. It’s a cancer that eats you alive from the inside out. So what I’m saying is that forgiveness is a process, often one that takes a long time. First we hurt, then we hate, then we heal ourselves, and then, if at all possible, we come together.

True forgivers don’t pretend they don’t suffer. They don’t pretend the wrong doesn’t much matter. But they do experience the transforming grace of God that brings them into the place of freedom and release. Which brings us back full circle, to Jesus saying, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

As we approach Holy Week, we remember that God risked everything when coming to this earth. God offered an open hand and we in turn offered a clenched fist. Jesus threw all his trust on God to exonerate him when he was on the cross. He nearly lost heart with his wrenching cry, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me.” But God trumped all human wickedness and restored lost trust on Easter morning when Christ was exonerated in his resurrection. Forgiveness, human or divine, is not cheap. It’s very costly. But it’s worth its weight in gold.

As we approach Holy Week, we remember that God risked everything when coming to this earth. God offered an open hand and we in turn offered a clenched fist. Jesus threw all his trust on God to exonerate him when he was on the cross. He nearly lost heart with his wrenching cry, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me.” But God trumped all human wickedness and restored lost trust on Easter morning when Christ was exonerated in his resurrection. Forgiveness, human or divine, is not cheap. It’s very costly. But it’s worth its weight in gold.